There are approximately 10 million people in the UK alone suffering from some form of arthritis. This disease of the musculoskeletal system presents itself in a wide range of form, with over 100 different classifications.

In general, arthritis symptoms include joint inflammation, stiffness, pain, and impaired function. There are a wide range of joints and surrounding tissues that can be affected, eventually leading to joint instability, deformation, and lack of mobility if not properly managed.

Unfortunately, at this stage there is no 100% cure for any type of arthritis, including the prevalent osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Nevertheless, there has been significant research into combination therapies that are making living with arthritis more manageable. In addition to medications, occupational therapy, and natural supplements, more people are subscribing to an arthritis diet consciously eating more of some foods and less of others.

How Important Is Diet For Arthritis?

Like many diseases, our diet affects our body’s ability to deal with arthritis. There are some foods which exasperate symptoms, while others can help to alleviate symptoms. By paying attention to the types of foods consumed, it’s possible to better manage arthritis.

There are several key dietary recommendations for people with arthritis:

- Maintain a well-balanced diet to support general health. A poor diet will not only negatively affect arthritis symptoms, it may also accelerate the progression of the disease and make the body more susceptible to other health problems.

- Avoid fasting or crash diets that place added strain on the body

- Increase calcium intake to minimise the risk of developing osteoporosis

- Maintain healthy fluid intake, drinking plenty of water.

- Keep bodyweight within a healthy range. Too much weight places extra stress on the joints, especially the hips and knees.

While these are good general guidelines, any arthritis diet should also focus on reducing inflammation, strengthening bones and cartilage, and reducing oxidative stress by elevating antioxidant intake.

The Problem With Inflammation

One of the key considerations in any arthritis diet plan is to avoid foods that promote inflammation. This especially applies to people already diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, gout, lupus, or ankylosing spondylitis.

What Causes Inflammation?

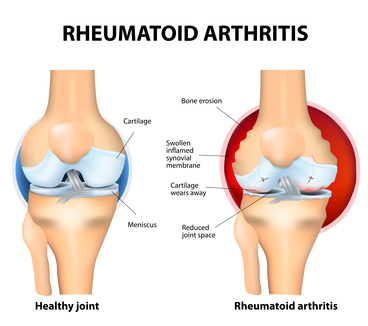

One of the underlying causes of these arthritic diseases is inflammation. When joints become inflamed they attract more inflammatory agents and white blood cells that cause further irritation. This causes the synovium (joint lining) to swell and leak into the surrounding tissues.

This swelling causes the joints to become stiff, restricting movement and causing pain and discomfort. As a result the cartilage and bone can start to breakdown and thin, further aggravating the joints and leading to disease progression.

This swelling causes the joints to become stiff, restricting movement and causing pain and discomfort. As a result the cartilage and bone can start to breakdown and thin, further aggravating the joints and leading to disease progression.

By gaining greater control over inflammation, it’s possible to reduce swelling. This will naturally reduce pain and discomfort, improving mobility and slowing joint degradation.

Controlling COX-1 & COX-2 with NSAIDs

One of the major underlying causes of joint inflammation are the enzymes cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). These enzymes trigger the release of prostaglandins, key hormones that elevate inflammation.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are prescribed to block COX-2, acting as inhibitors to inflammation. However, long-term use of these drugs has detrimental side effects.

There is now a large shift towards natural compounds that can help reduce inflammation in combination therapies to treat arthritis.

Preventing Inflammation With An Arthritis Diet

The relationship between diet and arthritis inflammation is a very important consideration in any patient’s diet plan. Food contains different nutrients and other compounds that can impact inflammation both positively and negatively.

Some substances will aggravate inflammation, while others can help to minimise inflammation. Understanding which foods to avoid and which foods to include in your diet for arthritis can make a significant difference.

Strengthening Bones and Joints

Many people that suffer from arthritis are also at risk of developing osteoporosis. Therefore, any arthritis diet foods should contain nutrients that support the strengthening of the joints and bones.

Many people that suffer from arthritis are also at risk of developing osteoporosis. Therefore, any arthritis diet foods should contain nutrients that support the strengthening of the joints and bones.

Calcium, vitamin K2 (menaquinone), vitamin D, phosphorus, magnesium, and manganese are all important nutrients that support healthy bones and joints.

Calcium is essential for maintaining bone mass. However, for the body to effectively utilise calcium it needs the support of other nutrients.

Increasing Antioxidant Availability

Research shows that there is increasing evidence that oxidative stress plays a major role in the degradation of joints affected by rheumatoid arthritis16. Chronic inflammation is closely linked to elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause cellular damage17.

Research shows that there is increasing evidence that oxidative stress plays a major role in the degradation of joints affected by rheumatoid arthritis16. Chronic inflammation is closely linked to elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause cellular damage17.

Not only does oxidative stress promote inflammation, it also has a direct impact on the joints by attacking important components of the structural tissue, such as proteoglycans, and stoping their synthesis18. Therefore, any rheumatoid arthritis diet plan should include plenty of antioxidants to try and reduce free radical activity.

An easy way to naturally increase dietary antioxidant intake is to eat an assortment of colourful vegetables and fruits each day. These foods are rich in anti-inflammatory antioxidants such as vitamin E, A, and C.

Other key antioxidant is the trace element selenium, which can be found in lean meats, seafood, poultry, peas, beans, eggs, seeds, and nuts. Copper, zinc, manganese, and iron are also important nutrients that can have antioxidant benefits due to their associated enzymatic activity with superoxide dismutases.

Dietary Supplements

In addition to eating antioxidant rich foods there are plenty of supplements available that are enriched with essential nutrients that can reduce oxidative stress and associated inflammation. These joint care supplements are an important aspect of an rheumatoid arthritis diet plan.

What Foods Should You Avoid With An Arthritis Diet?

Everybody will react differently to various foods and there is no “perfect” arthritis diet. However, many people with arthritis should foods that are known to irritate inflammation.

Watch this short video for the 5 worst foods for arthritis

References

- “Crowson, C. et.al. (2011). The lifetime risk of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis and Rheumatology, Volume 63, Issue 3, (pp. 633-9).” ↩

- “Artemis, P. and Simopoulos, M. (2002). Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. Volume 21, Issue 6.” ↩

- “Geusens, P. et.al. (2005). Long-term effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in active rheumatoid arthritis. Volume 37, Issue 6, (pp. 824-9).” ↩

- “Yan, Y. et.al. (2013). Omega-3 fatty acids prevent inflammation and metabolic disorder through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Immunity, Volume 38, Issue 6, (pp. 1154-63).” ↩

- “Calder, P. (2013). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: nutrition or pharmacology? British Journal of Clinical Phamacology. Volume 75, Issue 3, (pp. 645-62).” ↩

- “Yunsheng, M. et.al. (2006). Association between dietary fiber and serum C-reactive protein. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Volume 83, Issue 4, (pp. 760-6).” ↩

- “Ajani, U. et.al. (2004). Dietary fiber and C-reactive protein: findings for national health and nutrition examination survey data. Volume 134, Issue 5, (pp. 1181-5).” ↩

- “Friso, S. et.al.(2001). Low circulating vitamin B(6) is associated with elevation of the inflammation marker C-reactive protein independently of plasma homocysteine levels. Circulation. Volume 103, Issue 23, (pp. 2788-91).” ↩

- “Huang, et.al. (2010). Vitamin B6 supplementation improves pro-inflammatory responses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 64, (pp. 1007-13).” ↩

- “Kanpen, M. et.al. (2013).Three-year-low-dose menaquinone-7 supplementation helps decrease bone lose in healthy postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis International. Volume 24, Issue 9, (pp. 2499-507).” ↩

- “Cockayne, S. et.al. (2006). Vitamin K and the prevention of fractures: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Achieves of Internal Medicine, Volume 166, Issue 12, (pp. 1256-61).” ↩

- “Ishida, Y. (2008). Vitamin K2. Clinical Calcium, Volume 18, Issue 10, (pp. 1476-82).” ↩

- “Strause, L. and Saltman, P.(1987). “Role of Manganese in Bone Metabolism.” In: Nutritional Bioavailability of Manganese. American Chemical Society, (pp. 46-55).” ↩

- “Castiglioni, S. et.al. (2013). Magnesium and Osteoporosis: Current State of Knowledge and Future Research Directions. Nutrients. Volume 5, (pp. 3022-33).” ↩

- “.Rheaume-Bleue K. (2011). Vitamin K2 and the Calcium Paradox: How a Little-Known Vitamin Could Save Your Life. 1st ed. Ontario, Canada; Wiley.” ↩

- Wruck, C. et.al. (2011) Role of oxidative stress in rheumatoid arthritis: insights from the Nrf2-knockout mice. Annuals of Rheumatoid Diseases, Volume 70, Issue 5, (pp. 844-50).” ↩

- “Altidag, O. et.al. (2007). Increased DNA damage and oxidative stress in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical Biochemistry, Volume 40, Issue 3-4, (pp.167-71).” ↩

- “Hadjigogos, K. (2003).The role of free radicals in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Panminerva Med. Volume 45, (pp. 7-13).” ↩

- “Mazzon, E. et.al. (2001). Amelioration of Joint disease in a rat model of collagen induced arthritis by M40403, a superoxide dismutase mimitic. Arthritis Rheum, Volume 44, (pp.2909-210. ↩

- “Behaska, A. et.al (2002). Mechanism of vitamin E inhibition of Cyclooxygenase activity in mocrophage from old mice: role of peroxynitrite. Free Radical Biology Medicine, Volume 32, (pp. 503-11).” ↩

- “Helmy, M. et.al, (2001). Antioxidants as adjuvant therapy in rheumatoid disease. A preliminary study. Arzneimittel-Forschung, Volume 51, Issue 4, (pp. 293-298).” ↩

- “Jaswal, S. et.al. (2003). Antioxidant status in rheumatoid arthritis and role of antioxidant therapy. Clinica Chimica Acta International Journal of Clinical Chemistry, Volume 338, Issue 1-3, (pp. 123-9).” ↩

- “Darlington, L. and Stone, T. (2001). Antioxidants and fatty acids in the amelioration of rheumatoid arthritis and related disorders. British Journal of Nutrition, Volume 85, Issue 3, (pp. 251-269).” ↩

- “Hagfors, L. et.al. (2003). Antioxidant intake, plasma antioxidants an oxidative stress in a randomized, controlled, parallel, Mediterranean dietary intervention study on patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition Journal, Volume 30, (pp. 2-5).” ↩

- “Bae, S. et.al. (2003). Inadequate antioxidant nutrient intake and altered plasma antioxidant status of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Journal of American College of Nutrition. Volume 22, Issue 4, (pp. 311- 15).” ↩

- “Cerhan, J. et al. (2003). Antioxidant micronutrients and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in a cohort of older women. American Journal of Epidemiology. Volume 157, (pp. 345-54).” ↩

The use of antioxidant therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis has been a subject of many recent studies. Antioxidants such as vitamin E and superoxide dismutase have been successfully used in therapy to treat inflammation in animal experiments

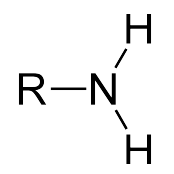

The use of antioxidant therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis has been a subject of many recent studies. Antioxidants such as vitamin E and superoxide dismutase have been successfully used in therapy to treat inflammation in animal experiments Glucosamine belongs to the class of amino sugars. Chemically it only differs from the glucose molecule by one amino group, which is not present in glucose.

Glucosamine belongs to the class of amino sugars. Chemically it only differs from the glucose molecule by one amino group, which is not present in glucose. Glucosamine is thought to relieve pain and inflammation and help in the formation of new cartilage tissue. This has been confirmed by many orthopaedists in practice.

Glucosamine is thought to relieve pain and inflammation and help in the formation of new cartilage tissue. This has been confirmed by many orthopaedists in practice. In 2012 Selvan and colleagues tested the influence of glucosamine sulphate and a combination of glucosamine sulphate with anti-inflammatory drugs. Their subjects suffered from mild to moderate osteoarthritis

In 2012 Selvan and colleagues tested the influence of glucosamine sulphate and a combination of glucosamine sulphate with anti-inflammatory drugs. Their subjects suffered from mild to moderate osteoarthritis  If glucosamine is used at an early stage and over a long period of time, it can potentially reduce the need to take anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs). Importantly, this means that the side effects of pain killers are reduced. Ultimately, this improves the quality of life of those affected.

If glucosamine is used at an early stage and over a long period of time, it can potentially reduce the need to take anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs). Importantly, this means that the side effects of pain killers are reduced. Ultimately, this improves the quality of life of those affected. The combination of glucosamine with other substances frequently leads to an altered effect. For example, when glucosamine sulphate is administered in combination with omega-3 fatty acids or vitamins, its effect seems to be stronger

The combination of glucosamine with other substances frequently leads to an altered effect. For example, when glucosamine sulphate is administered in combination with omega-3 fatty acids or vitamins, its effect seems to be stronger